´ ´

|

|

|||

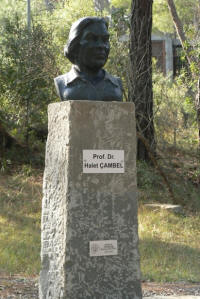

| Halet Çambel * 27. August 1916 in Berlin .jpg) Halet

Çambel is without a doubt the best known Turkish archaeologist. She is one

of the most important researchers for primeval and ancient history and the

most knowledgeable Turkish Hittite expert. Halet

Çambel is without a doubt the best known Turkish archaeologist. She is one

of the most important researchers for primeval and ancient history and the

most knowledgeable Turkish Hittite expert. Halet is born as the third child of Hasan Cemil Çambel and Remziye Çambel. Her mother, Remziye Hanım, is the daughter of the former Grand Vizier and the current Turkish ambassador, Ibrahim Hakkı Paşa, in Berlin. Her father, Hasan Cemil Bey, is the Turkish military attaché for Germany and a good friend of Atatürk. After the First World War the family lives in Switzerland, Austria and Tyrol for some years, because of the treaty of Sèvres and the following occupation of the Ottoman empire. They are only able to return to Turkey after the founding of the Turkish republic. Regarding these times, the little girl and her siblings Perihan, Leyla and Bülent grow up in a distinctly liberal environment. Their father's closeness to Atatürk, whose efforts lead to the end of the feudal Ottoman rule in Turkey and transform the country into a secular and democratic republic, also moulds the Çambel's family live. Halet will grow up to be a cosmopolitan, multilingual and tolerant woman. Halet Çambel remembers: "I was born and have lived in Berlin. My father was the military attaché for the German embassy in Berlin. My father could not come back, because the country was occupied. So the family had to wait until Turkey was declared a republic. Thus we came back in 1923/24. Coming back here I was eight years old. And we were shocked by the black shrouded women who came and visited us at home, too. My sister and I went to my mother and said: We don't want to stay here, we want to go back to Meran." The culture is strange to her, religion too different. The strict division of state and religion in Turkey is due to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the state in 1923. Atatürk is the first to drive his country towards the west. He replaces the sharia, the Islamic law system, with an Europe oriented judicial system and the Arabic alphabet with Latin letters, a new dress order leads to the gradual disappearance of the 'black aunts' of Halet's earliest memories. Halet Çambel is one of the last eye witnesses of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's revolution: .jpg) "Then

the Latin alphabet was introduced and it was a wonderful thing for us, too,

because one had to study six years to learn the old Turkish writing. After

that came the schools. Courses were held to learn the new writing for those

who could not read and write. In front of the schools one could see little

girls leading their grandparents by the hand to the school to learn." "Then

the Latin alphabet was introduced and it was a wonderful thing for us, too,

because one had to study six years to learn the old Turkish writing. After

that came the schools. Courses were held to learn the new writing for those

who could not read and write. In front of the schools one could see little

girls leading their grandparents by the hand to the school to learn." She herself absolves middle and secondary grade in the high school for girls in Arnavutköy, where her family has moved into a spacious Köşk (Form of Villa), made of red wood on the Bosporus. At least then it was situated directly on the sea front, nowadays a noisy big motorway is dividing it from the water. Halet Çambel still lives there. A wide stairway leads to the upper floor. Books and magazines are piled high on the steps, rooms and halls are filled with mahogany furniture, faded Japanese screens and other souvenirs of a widely travelled, polyglot family. Since moving here in 1930 Çambel starts to train fencing at the nearby English spoken Robert-College. As a fencer taking part in the Berlin Games in 1936, she is one of the first Turkish women participating in Olympic Games. This brings an unusual turn in her life. Çambel has to smile: "It started during a stay in France. I should have been going back to Istanbul, but then I was called to Budapest to participate in the Berlin games. Our coach was a German girl, a swimmer. She told us: I will introduce you to Hitler. But we just told her not to." For the Turkish fencers the 1936 Olympic adventure ends without medals. Nevertheless through their participation the young girls give the world an impression about how much the country has changed. Henceforth Halet Çambel dedicates her life to her academic career. At the Sorbonne in Paris she studies archaeology as well as Middle Eastern Languages (Hittite, Assyrian, Hebrew), at the time subjects dominated by German scientists in Turkey. Her familiarity with German culture is an asset for her during her studies and in her later professional life: .jpg) "When

my father was a young officer he was sent to Germany for his education. And

the staff officer in Berlin told them: 'Gentlemen, first you will learn to

sharpen your pencils. Because if you will mark a point on the map with a

blunt pencil, the shot will miss the goal.' They had to sharpen pencils for

a week. These are the things one has to achieve, to be meticulous in your

work ." "When

my father was a young officer he was sent to Germany for his education. And

the staff officer in Berlin told them: 'Gentlemen, first you will learn to

sharpen your pencils. Because if you will mark a point on the map with a

blunt pencil, the shot will miss the goal.' They had to sharpen pencils for

a week. These are the things one has to achieve, to be meticulous in your

work ." Returning to Turkey she marries the six years older known poet and later architect, Nail Çakırhan, with whom she will spend the next 70 years of her life in her parental home in Istanbul. Nail Çakırhan passed away only recently, in October 2008. Her family is against her liaison with a communist poet; they marry in secret and their relationship will become a symbol for a tolerant, respectful and fruitful marriage. They don't want children of their own, their life is satisfying, rich and lively. By now Halet Çambel has lived an academic career that tells a tale of the tradition of Turkish-German cooperation, the history of the still young Turkish republic and of the life of a modern woman in Turkey. She begins to work as an assistant in the Istanbul Faculty for Literature in 1940 and achieves her doctor title from there. Afterwards she goes to the Saarbrücken University as guest lecturer. "I would have liked to have more time. From university I passed directly into my professional life. Then all this bureaucracy. The lack of time to do something else." _small.jpg) In

the beginning of the 1950's new findings in the antique Hittite city of

Karatepe, close to Kadirli in the province of Osmaniye, are decisively

influencing her career. Initially as scholar of the German Professor

Helmuth

Theodor Bossert, she participates in the Karatepe-Aslantaş project and

contributes significantly to the further research of the Hittite language.

Furthermore she works closely together with Kurt Bittel, the later President

of the German Archaeology Institute. In 1960 Halet Çambel accepts

professorship for prehistoric at the Istanbul University. She receives

numerous honours, among them the Honorary Doctorship of the Eberhard Karls

University in Tübingen and the Prince Claus Award; at the same time she is

member of the German Archaeology Institute. In

the beginning of the 1950's new findings in the antique Hittite city of

Karatepe, close to Kadirli in the province of Osmaniye, are decisively

influencing her career. Initially as scholar of the German Professor

Helmuth

Theodor Bossert, she participates in the Karatepe-Aslantaş project and

contributes significantly to the further research of the Hittite language.

Furthermore she works closely together with Kurt Bittel, the later President

of the German Archaeology Institute. In 1960 Halet Çambel accepts

professorship for prehistoric at the Istanbul University. She receives

numerous honours, among them the Honorary Doctorship of the Eberhard Karls

University in Tübingen and the Prince Claus Award; at the same time she is

member of the German Archaeology Institute. A quote of the Danish- German Ethnologist Ulla Johansen gives an impression of the pioneer efforts and the example function Halet Çambel gives to generations of students. Çambel and Bahadır Alım, another student of Bossert, had helped Johansen in 1957 in a quite unorthodox way to get into contact with the nomadic Aydınlı to conduct her field research: _small.jpg) "Since

there were no schools in the small villages in South- East Anatolia, Halet

and Bahadır felt obliged to teach the children of the nearby village, which

provided them with workers as well, for three hours each day. Parallel they

looked after the health of the villagers. Therefore many farmers came to the

excavation site. Despite being a good looking woman in her early forties,

Halet was always respected by the farmers. She wore practical trousers and

simple, high buttoned blouses, completely covering her upper arms and a

man's cap on her short cut hair. She always told the farmers what she wanted

and planned to do in a straight forward unpretentious way. I copied Halet's

style ever after and never have been offended once, despite everything I

have been told before about Turkish men." "Since

there were no schools in the small villages in South- East Anatolia, Halet

and Bahadır felt obliged to teach the children of the nearby village, which

provided them with workers as well, for three hours each day. Parallel they

looked after the health of the villagers. Therefore many farmers came to the

excavation site. Despite being a good looking woman in her early forties,

Halet was always respected by the farmers. She wore practical trousers and

simple, high buttoned blouses, completely covering her upper arms and a

man's cap on her short cut hair. She always told the farmers what she wanted

and planned to do in a straight forward unpretentious way. I copied Halet's

style ever after and never have been offended once, despite everything I

have been told before about Turkish men." .jpg) Nail

Çakırhan follows his wife to Adana Karatepe in the 50's. The excavated

artefacts need a wide roof-covered space, where they can be restored,

protected and exhibited. A contractor already proceeded works, but has

abandoned the project, a new builder has not been found. The project,

designed by Turgut Cansever is handed over to Nail Çakırhan, together they

successfully finish the building. The first Turkish Open Air Museum has been

completed and with it the first wide roof-covered building made from visible

concrete. It could not stop there, the excavation house, the new precinct,

the buildings of the forest administration and schools for the region are

following. This creative period is so very typical for this loyal and

patriotic couple, Nail Çakırhan und Halet Çambel, who despite all attempts

to obstruct them still manage to get administrators, colleagues and

everybody else in their vicinity to cooperate successfully in each phase of

their lives. Nail

Çakırhan follows his wife to Adana Karatepe in the 50's. The excavated

artefacts need a wide roof-covered space, where they can be restored,

protected and exhibited. A contractor already proceeded works, but has

abandoned the project, a new builder has not been found. The project,

designed by Turgut Cansever is handed over to Nail Çakırhan, together they

successfully finish the building. The first Turkish Open Air Museum has been

completed and with it the first wide roof-covered building made from visible

concrete. It could not stop there, the excavation house, the new precinct,

the buildings of the forest administration and schools for the region are

following. This creative period is so very typical for this loyal and

patriotic couple, Nail Çakırhan und Halet Çambel, who despite all attempts

to obstruct them still manage to get administrators, colleagues and

everybody else in their vicinity to cooperate successfully in each phase of

their lives. While for her husband working on Karatepe means a real challenge and the founding stone for a new career as a later award winning architect, Halet will never again free herself from this excavation, which becomes the work of her life. Nowadays a museum building has been newly constructed beside the original open air museum, protecting the more sensitive artefacts. Of course the exhibition has been designed by herself. A marvellous grand picture volume bears witness to the productivity of half a century. The book she published together with a young colleague resumes decades of research work on Karatepe- Aslantaş; it not only documents the discovery and conservation of the gateways but contains a comprehensive and commented catalogue of all sculptures and reliefs as well as the iconographic research results of the depicted figures and scenes. The 'Bibliotheca Orientalis' describes the tome as follows: _small.jpg) "…

Halet Çambel and Asli Özizyar [have] presented a comprehensive Text- and

Picture Volume of the images for final publication. Besides a detailed and

richly illustrated study of the style and the iconography of all images, the

book also contains the history of their restoration and conservation, which

is, at the same time, the history of the construction of the open air museum

on Karatepe- Aslantaş. Without doubt this volume is one of the most

important new publications in the field of late Hittite research. It

provides access to an exemplary scientific process and the irresistible

print quality of the presented image material stimulates intensive

discussions."

In

the moment work is 'finished' by Halet in person and her younger colleague

Murat Akman, who is closely working with her for many years. They began the

great task to archive half a century of work at the Karatepe excavations.

Even now, while writing this

Halet Çambel died on 12.01.2014 and found her last peace next to her husband Nail Çakırhan at the cemetery in Akyaka |

||||

Compiled and written by: Bahar Suseven Edited by: Halet Çambel Some additional notes to the text: Karatepe-Aslantaş "Azatiwatas" _small.jpg) Karatepe, ("Black Hill") is a Late Hittite fortress and open air museum in the Osmaniye Province in southern Turkey. It is situated in the Taurus Mountains, on the right bank of the Ceyhan River. The site (Latitude: 37.258801N Longitude: 36.247601E) is part of the Karatepe-Arslantaş National Park. The images and inscriptions of Karatepe-Aslantaş were originally situated in two monumental Gatehouses in the northeast and southwest ramparts. The place was an ancient city of Cilicia which controlled the passage from eastern Anatolia to the north Syrian plain. It became an important Neo-Hittite centre after the collapse of the Hittite Empire in the late 12th century B.C.. The ruins of the walled city of king Azitawatas were excavated from 1947 onwards by Helmuth T. Bossert and Halet Çambel. Among the relics found here were historic tablets, statues and other remains; the most important findings being two monumental gatehouses with reliefs on their sills depicting hunting and war scenes and a boat with oars; statues of lions and sphinxes flank these gates. The site's eighth-century B.C. bilingual inscriptions, in Phoenician and hieroglyphic Luwian, trace the kings of

Adana from the "house of Mopsos",

written in hieroglyphic Luwian as Moxos and in Phoenician as Mopsos in the

form mps, have served archaeologists as a Rosetta stone for deciphering

Hieroglyphic Luwian. |

||||

_small.jpg)